The Last Days of the Schooner America

by David Gendell 14 May 2024 09:52 AEST

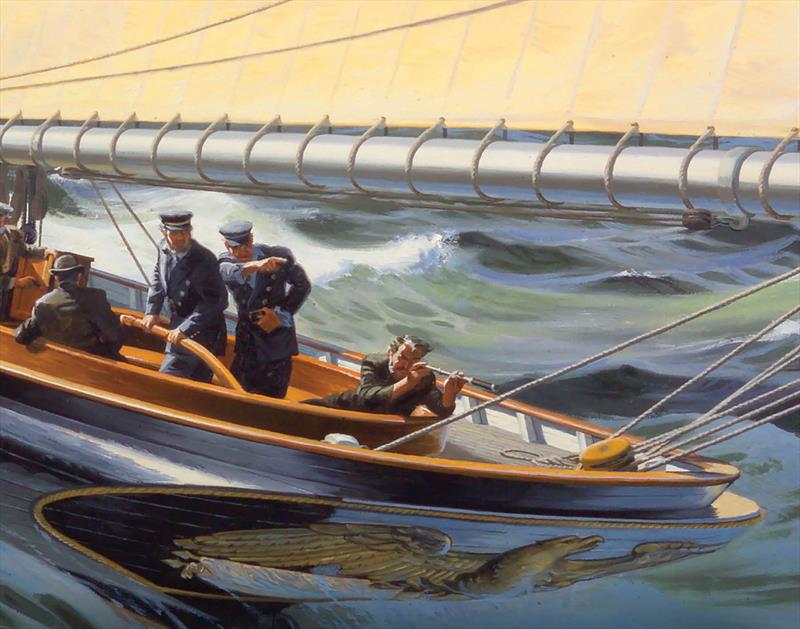

The Schooner America - A Lost Icon at the Annapolis Warship Factory © David Gendall

A Lost Icon at the Annapolis Warship Factory - The schooner America was a technological marvel and a child star. In the summer of 1851, just weeks after her launching at New York, she crossed the Atlantic and sailed to an upset victory against a fleet of champions. The silver cup she won that day is still coveted by sportsmen. Almost immediately after that famous victory, she began a decades-long run of adventure, neglect, rehabilitations, and hard sailing, always surrounded by colorful, passionate personalities.

America ran and enforced wartime blockades. She carried spies across the ocean. And she was on the scene as yachtsmen and business titans spent freely and competed fiercely for the cup she first won. By the early twentieth century, she was in desperate need of a thorough refit. The old thoroughbred floated in brackish water at the United States Naval Academy, stripped of her sails and rotting in the sun. Refitting America would be a massive project—expensive and potentially distracting for a nation struggling to emerge from the Great Depression and preparing for a world war. But the project had a powerful sponsor.

On a windy evening in December 1940, the eighty-nine-year-old America was hauled “groaning and complaining” up a marine railway at Annapolis: the first physical step in a rehabilitation rumored to have been set in motion by President Franklin Roosevelt himself. The haul-out brought the famous schooner into the heart of the Annapolis Yacht Yard, a privately owned company with a staff capable of completing such a project, but with leadership determined to convert their facility into a modern warship production plant on behalf of the United States and its allies.

The Last Days of the Schooner America traces the history of the famous vessel, from her design, build, and early racing career through her lesser-known Civil War service and the never-before-told story of her final days and moments on the ground at Annapolis. The schooner’s story is set against a vivid picture of the entrepreneurial forces behind the fast, focused rise of the Annapolis Yacht Yard as the United States prepares for and enters World War II. As wooden warships are built around her, America waits for a rehabilitation that would never happen. To bring this unique story to life, Annapolis sailor David Gendell delves into archival sources and oral histories and interviews some of the last living people who saw America at the Annapolis Yacht Yard.

About the Authors:

Sailor and author David Gendell is an Annapolis native with an extensive sailboat racing background. In 1995, he cofounded SpinSheet, a Chesapeake Bay sailing magazine, and served as its editor for twelve years. In 2004, he cofounded PropTalk, a Chesapeake Bay powerboating magazine. He is a Coast Guard–licensed captain and the author of Thomas Point Shoal Lighthouse: A Chesapeake Bay Icon, the first and only book devoted to the 1875 lighthouse. He lives in Annapolis, Maryland, and is a frequent public speaker in the Chesapeake Bay region on the subjects of sailing and history.

Gary Jobson served as tactician for Ted Turner’s 1977 America’s Cup defense aboard Courageous. As a broadcast journalist, Jobson covered nine America’s Cup matches for ESPN and won an Emmy award for his coverage of the 1988 Olympic Sailing event in South Korea. He is the author of twenty-three sailing books.

Excerpt

Chapter 28

“The most awful crash I ever heard”

March 29, 1942

Annapolis

Annapolis residents awoke on Palm Sunday to an unexpected layer of spring snow and an odd, transitory feeling in the air. As the morning unfolded, heavy, wet snow continued to fall from a leaden sky. Dark clouds scudded below the overcast layer, as if hastily drawn with a scribble of charcoal and then animated in high speed. Occasional rumbles of distant thunder added to the spooky scene. The snowfall arrived in heavy bursts and then, just as quickly, dropped away to flurries, some- times stopping and then restarting several times within the span of a minute. A contract for a second wave of Annapolis Yacht Yard Motor Torpedo Boats had been executed, and despite the foul weather there was plenty of work to do at the plant and no shortage of inspiration in the air. Pearl Harbor had been attacked just 112 days earlier and the sting remained fresh.

The plant’s initial pair of Sub-chasers floated unfinished in the cold water, alongside new piers. Nearby, in the plant’s wooden and concrete sheds, the first nine Annapolis Motor Torpedo Boats were rapidly taking shape. Stacked and waiting alongside this unfinished fleet was a virtual shipbuilder’s catalog of prebuilt parts, sections, and bits, all destined to become part of the finished vessels.

A small crew of men—fourteen in total—traveled through the sur- prise snow for a Palm Sunday morning shift at the Yacht Yard, including crew boss Joe Dawson and yard superintendent Lyle Gaither. The plant’s electricity was still on, they were relived to discover. The promise of heat and access to power tools would both make this shift more bearable. As each man arrived, he punched in his time card and inserted it into the face of a varnished rack. Fourteen was enough men to get the day started but more were always needed. It is possible, perhaps even likely, that Joe Dawson’s seventeen-year-old son Dickie was among this crew. There was no school on a Sunday, and the opportunity to make some extra money is always appealing to a teenager. As the crew pulled on coveralls and reached for hot coffee, Dawson and Gaither assessed the scene. The odd weather would define the day’s tasks. Looking back on this morning, Dawson would later recall that “it was snowing as hard as you ever see in this world.”1

Clearing the snow off the top of the America shed stood at the top of the morning work list. In a heavy snow, the design of the new shed over the schooner threatened to betray the vessel it was built to protect. As the snow fell upon the broad roof of the Big Shed, the relatively warm air inside the building melted the snowpack just enough to cause it to slide down onto the top of the uninsulated, unheated America shed where it then piled wet and heavy. Upon their own arrivals at the plant that morn- ing Dawson and Gaither had each eyed the accumulated snow atop the shed with concern. They had to take action, immediately.2

Once coveralls were pulled on and coffee acquired, the crew gathered around Joe Dawson and Lyle Gaither and the two leaders explained the day’s goals. Dawson would take a small team to Twenty-One, now sit- ting, partly finished, in the Big Shed, for a depth sounder install. Gaither would move upstairs to the office to try to call in additional workers, and everyone else would grab shovels and ladders and get up on top of the America shed to clear off the growing piles of snow.

There were likely a few groans, but Lyle Gaither kept the crew focused. He assured his men: after clearing away the snow, they would shift inside for warmer, drier projects. But move, move toward the shovels, ladders, and the shed. Getting the snow off was a highest priority.

Joe Dawson lifted his toolbox and selected his two assistants, men who considered themselves lucky that they would not be shoveling on the roof. The smiling pair followed him over to Twenty-One and then into the narrow confines of her bow, which still smelled of new paint and fresh-cut wood. Twenty-One, the first and, at this point, the most com- plete Motor Torpedo Boat under construction at the Annapolis plant, served as a critical testbed. Work on the ship informed the operational details and timelines for the high-volume production run all hoped to achieve in the coming months. To that end, Dawson crawled into the confined space of the ship’s bow and began fitting the depth sounder. Along the way he planned to document the associated timing, mea- surements, and procedures. Looking forward from this morning, dozens, perhaps even hundreds of other depth sounders would be fit into other Annapolis-built warships. While today’s might be the first and last depth sounder personally installed by the plant’s crew boss, he was compelled to understand how the process unfolded and how long it should take.

Meanwhile, Lyle Gaither stepped up the nearby wooden stairs that connected the open space of the Big Shed with the plant’s second-floor offices. As he moved into a chill, dark office he thought about who else he might call and ask to come in on a snowy Sunday morning. Once the America shed was cleared there was plenty of inside work and more hands were always welcome. When he reached the office and lifted the telephone, he was relieved to find that the phone lines had not yet been cut by the storm damage.

Outside, on the ground and in the cold, the balance of the crew fanned out across the property, searching for ladders, shovels, and any- thing else that might help them move heavy, wet snow off the shed roof. Moments later, from inside the bow of the Motor Torpedo Boat and from an upstairs office, Dawson and Gaither each heard a loud boom followed immediate by a crunch. They both knew that the shed over America had collapsed. For the rest of his life, Joe Dawson was asked to tell the story of this morning. Decades later he explained that he heard the collapse clearly from inside the bow of the Motor Torpedo Boat: “I was scrunched down up there . . . when there was the most awful crash

I ever heard.”