North West Passage- Open for Boats - and Business

by Scott G. Borgerson/Sail-World /Powerboat-World on 1 Mar 2008

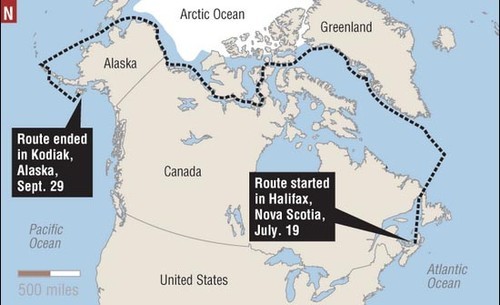

Route sailed by photographer David Thoreson on Cloud Nine last year David Thoreson

http://bluewaterstudios.com/

The news that the North West Passage is fast melting might be glad news for the pleasure boating community and the commerical marine traffic, but is potentially bad news for the wildlife of the region, and sad news for the ordinary guy who wants to keep the planet's remaining natural regions safe from the onslaught of the Western World.

Recently we published a story of how the crew of Cloud Nine, which sailed the route last season, found little ice to block their way. Photographer David Thoreson, alarmed by the change, reported that he felt like 'the canary returned from the coalmine.'

Now Scott G. Borgerson, International Affairs Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and a former Lieutenant Commander in the U.S. Coast Guard, writes of the glad/bad/sad news of the opening of this once forbidden route to the Pacific.

The Arctic Ocean is melting, and it is melting fast. This past summer, the area covered by sea ice shrank by more than one million square miles, reducing the Arctic icecap to only half the size it was 50 years ago. For the first time, the Northwest Passage -- a fabled sea route to Asia that European explorers sought in vain for centuries -- opened for shipping. Even if the international community manages to slow the pace of climate change immediately and dramatically, a certain amount of warming is irreversible. It is no longer a matter of if, but when, the Arctic Ocean will open to regular marine transportation and exploration of its lucrative natural-resource deposits.

The Arctic has always experienced cooling and warming, but the current melt defies any historical comparison. It is dramatic, abrupt, and directly correlated with industrial emissions of greenhouse gases. In Alaska and western Canada, average winter temperatures have increased by as much as seven degrees Fahrenheit in the past 60 years. The results of global warming in the Arctic are far more dramatic than elsewhere due to the sharper angle at which the sun's rays strike the polar region during summer and because the retreating sea ice is turning into open water, which absorbs far more solar radiation. This dynamic is creating a vicious melting cycle known as the ice-albedo feedback loop.

Each new summer breaks the previous year's record. Between 2004 and 2005, the Arctic lost 14 percent of its perennial ice -- the dense, thick ice that is the main obstacle to shipping. In the last 23 years, 41 percent of this hard, multiyear ice has vanished. The decomposition of this ice means that the Arctic will become like the Baltic Sea, covered by only a thin layer of seasonal ice in the winter and therefore fully navigable year-round. A few years ago, leading supercomputer climate models predicted that there would be an ice-free Arctic during the summer by the end of the century. But given the current pace of retreat, trans-Arctic voyages could conceivably be possible within the next five to ten years. The most advanced models presented at the 2007 meeting of the American Geophysical Union anticipated an ice-free Arctic in the summer as early as 2013.

The environmental impact of the melting Arctic has been dramatic. Polar bears are becoming an endangered species, fish never before found in the Arctic are migrating to its warming waters, and thawing tundra is being replaced with temperate forests. Greenland is experiencing a farming boom, as once-barren soil now yields broccoli, hay, and potatoes. Less ice also means increased access to Arctic fish, timber, and minerals, such as lead, magnesium, nickel, and zinc -- not to mention immense freshwater reserves, which could become increasingly valuable in a warming world. If the Arctic is the barometer by which to measure the earth's health, these symptoms point to a very sick planet indeed.

Ironically, the great melt is likely to yield more of the very commodities that precipitated it: fossil fuels. As oil prices exceed $100 a barrel, geologists are scrambling to determine exactly how much oil and gas lies beneath the melting icecap. More is known about the surface of Mars than about the Arctic Ocean's deep, but early returns indicate that the Arctic could hold the last remaining undiscovered hydrocarbon resources on earth. The U.S. Geological Survey and the Norwegian company StatoilHydro estimate that the Arctic holds as much as one-quarter of the world's remaining undiscovered oil and gas deposits. Some Arctic wildcatters believe this estimate could increase substantially as more is learned about the region's geology. The Arctic Ocean's long, outstretched continental shelf is another indication of the potential for commercially accessible offshore oil and gas resources. And, much to their chagrin, climate-change scientists have recently found material in ice-core samples suggesting that the Arctic once hosted all kinds of organic material that, after cooking under intense seabed pressure for millennia, would likely produce vast storehouses of fossil fuels.

To read the full article by Borgerson, go to http://www.foreignaffairs.org/20080301faessay87206/scott-g-borgerson/arctic-meltdown.html

If you want to link to this article then please use this URL: www.sail-world.com/42232