Traditional Marquesas – On Its Deathbed?

by Nancy Knudsen on 10 Jul 2007

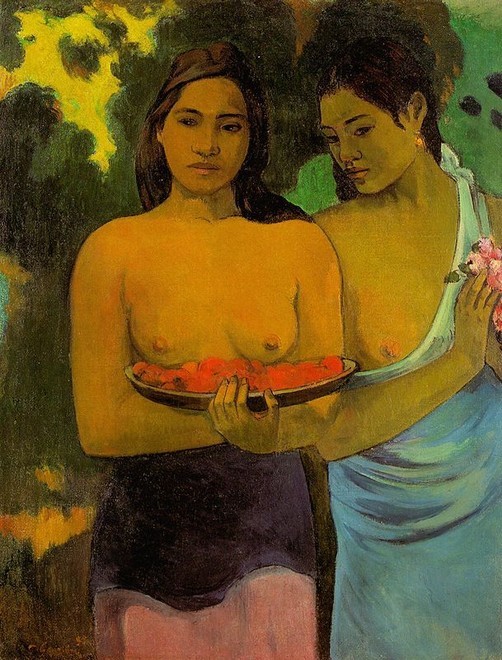

Gauguin SW

One of the delights for the long range cruising sailor is the opportunity to meld into a local culture for a while to discover, to learn, to appreciate. We had yet another one of these opportunities recently in the Marquesas and came away with mixed emotions.

The Marquesas of Paul Gaugin and Herman Melville is painted as sometimes heavenly, sometimes horrifying, but always exotic and always fascinating – a far-off nirvana with the occasional tiny flaw like cannibalism.

The arrival of Europeans had a dramatic effect, some positive, most negative. The missionaries ended cannibalism and clothed the women, the influx of other Europeans decimated the population with disease, reducing the population from an estimated 80,000 to today's 8,000. At its worst, the population was under 3,000.

Even so, as you walk the lanes and pathways of modern Marquesas, the images inspired by both Gaugin and Melville are still there – the rich beauty of the young women, flowers behind ear, the lushness of waving palm trees and rain forests, the soaring cliffs forever above, the tranquil pace of the lifestyle.

However, after the first rush of elation at the amazing beauty all around, questions come to mind that keep insisting on answers, and a different Marquesas emerges. Some of the answers are so disturbing that one is inclined to ask: Is the old Marquesas on its deathbed?

French visitors to the islands harrumph when they stare about at the good roads, electricity and young men playing basketball midweek on the foreshore. 'So this is what my taxes are paying for....'

It's true that the economy is heavily subsidised by France. Marvelous concrete roads snake across the high volcanic countryside of the most populated island, Nuku Hiva, and more are being built. This is employment for the Marquesans, and according to the locals there's hardly any employment on the island these days, except for government jobs. The main industry, copra, is weak at best.

'There aren't any jobs for the young people,' says an Englishman who has lived here for 14 years, 'but then there's no incentive for them to work anyway, as you just can't go hungry here. Everyone has an extended family which may stretch across all the islands in the Marquesas, so there is always somewhere to sleep.

The fruits and vegetables available both in the wild and around their houses are more than they can eat. The weather is kindly, they can go fishing, there are wild chickens, pigs and goats for the hunting, and with this weather they need few clothes. They actually don't NEED a job. A job merely provides luxuries – luxuries that they can easily do without.'

Part of the largesse, we are told, stems from the comparatively small population today – when the population was as large as the quoted 80,000, survival was more difficult, and there were sometimes famines.

With the decline in the population, the planted fruit trees now growing wild, the wild goats and pigs, not to mention the wild chickens that you hear crowing in every deserted anchorage, provide this world of plenty that we hear about.

This sounds almost too idyllic to be true, but it is borne out by our experiences. As a visiting cruiser, all you need to do is go walking among the sweet simple houses, spy some fruit – grapefruit, bananas, papaya, breadfruit, mangoes, not to mention coconuts – and ask the householder if you can buy some.

Much of the time they won't hear of taking payment – they have so much they end up piling you up with more fruit and vegetables than you can carry. It's a land of plenty, and this even shows in the peaceful expressions of the people who amble – no-one rushes - around the streets – the mothers come to the shore with their babies to gossip on the grassy esplanade, the children roam unchaperoned and the lovers stroll as lovers do, holding hands.

This sounds like the heaven we all think of in the South Pacific, but then something happens to dent our impressions.

While we are there, the biggest day of the year arrives – Autonomy Day – the day that they celebrate, not independence from France, but at least autonomous rule. We look forward to hearing some Marquesan music, seeing some local dancing, and the promised local celebratory food, so we eagerly attend the celebrations in a huge quickly built hall, specially constructed for the occasion.

We arrive with anticipation, entranced by the woven palms round all the internal pillars. 'made by the older ladies – the mamas' we are told. There are locally designed fabrics on the walls, wonderful rich colours – also provided by the mamas.

But apart from the décor, the evening is as exciting as a local countcil meeting, and we could be anywhere in the world. The food is vaguely Indian, or you can choose hot dogs if you prefer, the drinks are Coca Cola, beer and cheap French wine. The music comes from a tape deck, and the dancing turns out to be Tahitian, with a dollop of Egyptian belly dancing.

Whereas we were looking forward to seeing traditional costumes, with examples of seed costumes, all the costumes are made of fabric, quick and easy.

The drum beats also come from a loud speaker, and after the Tahitian/Egyptian performers, a Disco is announced – but nobody dances except the children, who have a wow of a time, skating across the concrete floor of the hall, screaming in competition with the music, as kids will do anywhere given a chance.

We later learn that all the energy for making of seed decorations goes into making necklaces for the tourist market – again by the mamas. A large display hall has been erected for the benefit of the tourists on cruise ships, and modern marketing has dictated that even the nature of the seed necklaces has been changed to suit the popular tastes of the tourists.

I ask another local European, who came here as a cruiser 35 years ago and never left, why we have not seen traditional dancing or costumes, even on their most revered day of the year. The answer I receive seems to sum up the downside of modern Marquesas. 'It's all gone, and it is a pity - they are spoilt you know,' she says. 'France provides everything they need, they have to try for nothing. What France does not provide, the island does. It is more than laid back – I would call the people today indolent. And with the indolence, the old traditions are disappearing fast – it's very disappointing for us who came here loving the Marquesas as it was.'

Disappointing? Yes, but on recollection, maybe what she says is indicative of trends noticeable in so many other countries and communities – more and more dependence on central authorities, more and more homogenisation.

Nevertheless, as we say goodbye to the Marquesas and sail on to other destinations, we are still sad to see this one further example of an ever more common world wide theme.

If you want to link to this article then please use this URL: www.sail-world.com/35527