From Bare Poles to Paradise (but Why?)

by Dianne Nilsen/Sail-World Cruising on 18 Mar 2007

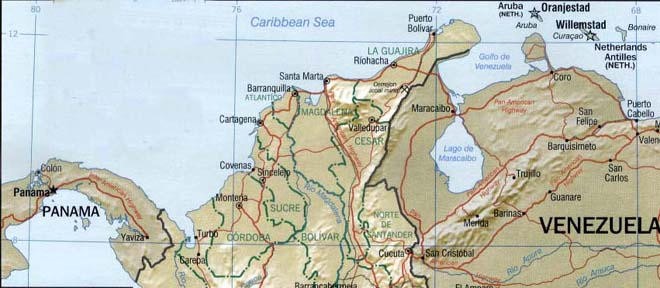

Colombian coast between Bonaire and San Blas Islands, Panama. SW

Being wise after the event is not a difficult task. However, if the goal of reading other people’s experiences is to improve one’s seamanship, any story of hardship at sea deserves to be examined for lessons. Sometimes, an alarming story retold often can give a sailing area an undeserved reputation, and discourage others from sailing the area.

In June last year, Caribbean Compass, a monthly local Caribbean newspaper, published an article which has become many times retold, and has had the effect of frightening as many cruisers as possible away from the coast of Colombia. It was written by some cruisers, the Nilsons in Vula, about a journey they had from Bonaire in the Netherlands Antilles to San Blas, those magical coral atolls off the coast of Panama.

Reading the excerpt of the story that relates to their bad experience in Colombian waters, what questions would YOU ask about their seamanship? Then compare them at the end of the article with those we have posed. The article was titled ‘From Bare Poles to Paradise’:

On the 25th of March we left Bonaire, bound for San Blas, in Vula, our 31-foot, sloop-rigged, South African-built Morgan. We had come a long way since leaving South Africa, but this voyage was to truly test our endurance and the strength of our small boat.

We rounded the point of Colombia, 60 miles northwest of Barranquilla, on Monday, the 27th. The winds were up to 25 knots and increasing, with swells up to 15 feet. By 4PM, the winds were over 30 knots and, to our alarm, the swells were still increasing.

I served the two of us a hasty stew and was frantically stashing things away when something came adrift and knocked off our power supply, which switched off the autopilot, placing us broadside to a huge wave. We were lifted and pitched down the face of this 20-foot wave. Les shot outside to try and grab the tiller in time but it was too late.

The force of the knockdown sheared off the rudder to the autopilot. I was thrown into the electrical panel and stew flew everywhere. The fridge became dislodged and went flying in the opposite direction, spilling all its contents, while a ton of sea water came hurtling straight over the stern and down into the boat. What a mess! Les later confessed that what he saw happening below from his position in the cockpit was very scary and he had a daylight nightmare of being both wifeless and fridgeless.

What were we involved in here? We had done everything correctly and had received weather information from a friend in Bonaire before we left. We'd been told that it was the best weather predicted for the Colombia coast in a long time, and it should have lasted for two or three days. In spite of the good predictions, we were in the middle of something bad and conditions were still picking up.

This was not supposed to be happening. The barometer dropped. Les reefed in the genoa to slow us down, as our hull speed is six knots, but we were topping seven to eight although well reefed in. The winds steadily increased so Les decided to bare pole it. This we did for more than 65 hours. The seas became so huge that we were surfing and logged a shattering 17 knots down waves, while averaging eight to ten knots. This was unbelievable to us but it was truly happening.

At this point we had to find a way to slow Vula down, as the shuddering was bone-jarring, horrendous, nightmare stuff. During the night, helming was another nightmare. You could hear the waves coming, feel them lifting you higher and higher before they hurled you careening down their backs. Les tied all our lines to the stern for drag, in an effort to slow us down. This helped to keep our speed to six or seven knots.

During the nights we were at the helm one hour on and one off. Daytime we managed two on and two off. We could not do more hours on the helm, as the stress and strain were just too much. At one point Les was hallucinating and had to keep shaking his head and slapping himself.

I could not and would not look back at the waves nor at our odometer - or even at Les, because the expression on his face and all the 'Holy shits!' were scaring the hell out of me.

At one point Les wanted to move the drogue to the bow of the boat so it would lie ahull - bow into the waves. I went ballistic and would not allow Les out of the cockpit, terrified of what might happen to him on that flying, wave-washed deck. I could not imagine him doing this.

At another point he wanted to head out northwest, and that meant motoring up and over the waves. I screamed that this was definitely NOT ON, as I had read and seen the movie 'The Perfect Storm' (and at that point, I wished I had not). We were both thinking and praying that this just could not last. Please, just another couple of hours and this madness would be over.

So many hours of feeling, sensing, concentrating on just steering and pulling out of waves were mind-numbing and, at night, the watching and steering our course to the compass, not wanting to go off by even a few degrees, was grueling.

I was thrown three times and have no idea how many times we were pooped. The hardest fall was head and feet into starboard lockers and then tossed back onto a bunk. Les, at the helm, was screaming 'Dianne! Speak to me!' That was all he could do, not daring to leave his position.

We did not get much sleep, as while lying down we had to wedge ourselves between lockers and the mast compression post. The only thing we managed to rest were our eyes. I was afraid to drift off in fear of losing my grip on things and getting thrown again. To sustain ourselves, we swallowed water, juice, crackers and vitamins.

On Friday the swells were down to 10 to 15 feet and the wind had dropped to 25 knots. Our speed had slowed to four or five knots, still under bare poles with the drogue lines out.

Les eventually took in the lines and just before sunset he let out some genoa and poled it out. He also made our first cup of hot coffee without incident. I felt we were going to survive after all.

How did you go? – Did the Nilsons do ‘everything correct’ as they claimed? Or what should they have done? - remembering, to be fair, that it is 20/20 vision hindsight. Here are our questions:

1. If the crew were ‘alarmed’ when the winds reached 30 knots, why were both crew inside the boat, with no-one in the cockpit watching the boat?

2. 'Something came adrift' - the story doesn't say what, but it underlines the importance of tying down securely.

3. The FRIDGE became dislodged? This sounds like questionable installation. The fridge is one very heavy item, and the idea of it being able to be dislodged by a knock-down leads one to question how this could happen. It’s certainly a heads-up to make sure that all heavy items on your boat are properly secured.

4. ‘Received weather information from a ‘friend in Bonaire’? On the face of it, this sounds very casual. HF, VHF and emailed weather, not to mention internet based information, are available and pretty accurate for this area – ‘from a friend’ does not sound very seaman-like. Most good seamen I know get at least three professional forecasts and compare them for whether they coincide. The information is also available up to several times a day. Were they relying on the one word-of mouth weather forecast received before they left port to transit an area known to be windy? No updates?

5. The story says that the barometer was going down – this is normal for Columbia, as there is a permanent low-pressure system located over Colombia, and probably not responsible for any unusual weather in the area. 'The two Capes' are known as one the windiest parts of the Colombian coast. Good seamen who had done their research would have known this before proceeding.

6. One must sympathise with the exhaustion that would come when caught without an autopilot and with a short-handed crew. But if the conditions

If you want to link to this article then please use this URL: www.sail-world.com/31782