Captain Cook’s Logs Key to New Compass Findings?

by John Roach, National Geographic/Sail-World on 13 May 2006

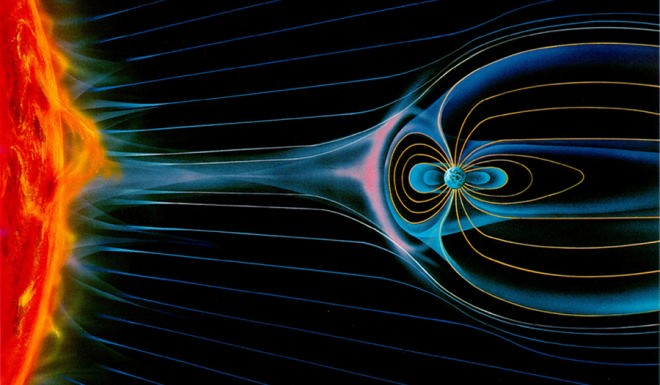

Earths Magnetic Field SW

If you’re ever wondering why your dead reckoning is out, or the magnetic compass is not agreeing with your GPS, a new analysis of old ships’ logs could hold the answer.

Sailors with a more than usual interest in accurate navigation will be interested to know these latest findings by a UK based Earth Scientist.

While it has been known for some time that the Earth's magnetic field is weakening, a new analysis of centuries-old ships logs suggests it is doing so in staggered steps.

The finding could help scientists better understand the way Earth's magnetic poles reverse.

The planet's magnetic field flips—north becomes south and vice versa—on average every 300,000 years. However, the actual time between reversals varies widely.

The field last flipped about 800,000 years ago, according to the geologic record.

Since 1840, when accurate measures of the intensity were first made, the field strength has declined by about 5 percent per century.

If this decline is continuous, the magnetic field could drop to zero and reverse sometime within the next 2,000 years.

But the field might not always be in steady decline, according to a new study appearing in tomorrow's issue of the journal Science. The data show that field strength was relatively stable between 1590 and 1840.

'It now looks as though it happens in steps rather than just one continuous fall,' said David Gubbins, an earth scientist at the University of Leeds in the United Kingdom.

The magnetic field protects Earth from cosmic radiation. In its absence, scientists say, Earth would be subjected to more electrical storms that disrupt power grids and satellite communications

To more accurately measure older samples of the field's rate of decline, Gubbins and his colleagues used new data from historic sources, including ships' logs.

The ships' logs provide information on declination—the direction compasses point—and, beginning around 1700, inclination—the angle a magnetic needle makes relative to the horizon.

Using statistics to combine intensity measurments starting in 1590 with the data from the ships' logs allowed the team to reduce the inaccuracies, Gubbins explained.

What they determined is that the field was relatively stable for about 250 years.

When Gubbins and his colleagues analyzed their data, they found that the most recent decline can be explained by patches of reverse magnetic field that have been growing in and migrating around the Southern Hemisphere since about 1800.

'It does look like the patches first formed toward the end of the 18th century, when Captain Cook was busy sorting out navigation and measuring magnetic field all over the world,' Gubbins said.

Captain James Cook was an English explorer famous for his voyages to the Pacific Ocean (Oceania map) and for mapping Australia's east coast, the Hawaiian Islands, Newfoundland, and New Zealand.

Glatzmaier agrees that the patches of reverse magnetic field are responsible for the measured decrease in field intensity over the past two centuries.

He added, however, that the patches are not the cause of the weakening magnetic field but rather a 'manifest of what is happening deep below in the core. The field is changing because of the dynamo well below the surface.'

The dynamo is the geologic process that creates the magnetic field, maintains it, and causes it to reverse.

Scientists believe the dynamo occurs where heat from the solid inner core churns the liquid outer core of nickel and iron.

Since the last field reversal about 800,000 years ago, the field has tried but failed to reverse somewhere between 10 and 20 times, Gubbins says.

'So the field [intensity] is continually zigzagging all the time,' he said

www.sail-world.com/send_message.cfm!Click_Here!same to write to us about this article

If you want to link to this article then please use this URL: www.sail-world.com/23836