Anatomy of a collision - yacht and bulk carrier

by Lee Mylchreest on 13 Dec 2013

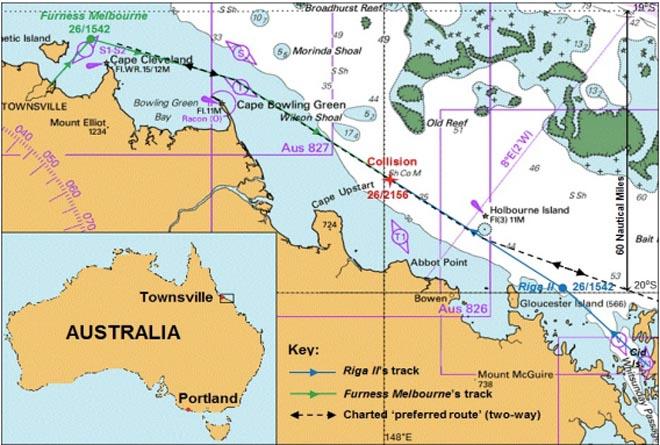

Furness Melbourne and Riga II -chart showing their respective courses SW

What are the factors most likely to cause a collision at sea? What mistakes should the cruising sailor NOT make? How much can we rely on a good lookout by ships that we pass? The investigation of this non-fatal collision between a Swiss-flagged yacht and an Australian bulk carrier carries some significant messages for how we should all act when sailing an open seaway.

Just before 10.00pm on 26 May 2012, the bulk carrier Furness Melbourne and the yacht Riga II collided about

15 miles north of Bowen, Queensland. Riga II was dismasted and its hull was damaged but no-one was seriously injured and the yacht was towed into Bowen on the Australia's Queensland coast by a volunteer marine rescue vessel.

Furness Melbourne was not damaged and, after rendering assistance to the yacht, continued its voyage. But the story is one that will cause a chill down the spine of many a cruising sailor.

About Riga II:

Riga II was a 13.6 m sloop rigged yacht constructed from aluminium and composite materials. The yacht was fitted with a diesel engine but, at the time of the collision, it was under sail and the engine was not being used.

Riga II was crewed by its owners (the skipper and his wife) and their friend. All three held a Swiss international certificate for operators of pleasure craft (Permit B). Each had more than 25 years of sailing experience in different parts of the world. Over that period, they had sailed together a number of times.

After purchasing Riga II in 2007, the skipper and his wife began sailing around the world in the yacht with their friend frequently accompanying them as circumstances permitted. In September 2011, their leisurely paced voyage brought them to Bundaberg, Australia. They returned to Europe for a few months before resuming their voyage in May 2012, after their friend and 11 year old grandson had joined them to sail north along the coast of Queensland.

The yacht’s navigational equipment included a SIMRAD CX-44 radar, a NASA MARINE AIS radar

receiver and two VHF radios (SIMRAD and ICOM).

What the ATSB found:

The investigation found that a proper lookout was not being kept on board either vessel in the time

leading up to the collision.

At the time of the collision the 13.6 m yacht Riga II was en route to Townsville. At 1542, the yacht was about 9 miles

east of Gloucester Island on a course of 303º (T) and making good about 6.5 knots. The skipper and his wife (the yacht’s owners), their friend and grandson were on board. They had sailed from Cid Harbour in the Whitsunday Islands earlier that afternoon on the first leg of a cruise to far north Queensland.

By 1930, Riga II had reached a position nearly 6 miles west of Holbourne Island, very close to the 123·5º - 303·5º charted ‘preferred route’ (see below for explanation). The yacht’s auto-pilot was set to make good its planned course of 303º (T) and the wind (15 to 20 knots from the south) was abaft the port beam. The starboard leeway meant that the heading varied between 295º and 300º.

The skipper was on watch, keeping a lookout while the others on board either rested or slept. While the yacht’s

automatic identification system (AIS) unit was switched on, the radar was switched off.

At this time, Furness Melbourne was on a 123º (T) course following the 123·5º - 303·5º preferred route in the opposite direction to Riga II. At 2000, when the third mate took over the bridge watch from the chief mate, the ship was about 42 miles west-northwest of Holbourne Island. The duty seaman on watch also changed. The weather conditions recorded in the ship’s log book noted ‘overcast skies, good visibility, fresh southerly breeze and rough seas’.

At 2051, the third mate began playing music on a personal computer. From time to time, he hummed or sang along with the music and, sometimes, chatted with the lookout. The visibility remained good and they could not see any ships or other traffic nearby. The s-band radar, AIS unit and both very high frequency (VHF) radios were switched on.

Shortly after 2100, the seaman reported a white light fine on Furness Melbourne’s port bow. The third mate told the seaman that the light was a distant lighthouse. At this time, Holbourne Island and Nares Rock, both of which were fitted with lights, were a little over 30 miles away

At about 2118, the lookout reported that the white light he had seen earlier was flashing. The third mate could see no radar targets in the general direction of the light and told the lookout that it was the distant lighthouse that he had previously mentioned.

At 2142, the seaman reported a green light fine on the port bow. The third mate thought the green light was from the isolated danger beacon on Nares Rock and he told the seaman that the light was a distant ‘light buoy’. In fact, the green light was the starboard sidelight of Riga II, which was about 4 miles away.

At 2144, the third mate adjusted Furness Melbourne’s heading to starboard from 123º to 128º, to pass further away from what he mistakenly believed was Nares Rock. At 2146, he adjusted the heading back to 125º and, 2 minutes later, again to 128º. He then adjusted the heading back to 123º. He sang and hummed along with the music as he had during the past hour.

At about 2149, Riga II’s AIS unit ‘target alarm’ sounded. Alerted, the skipper’s wife called the skipper to come inside the cabin and have a look at the AIS display. Together, they noted from the AIS data that the approaching ship was making good a course of 122º (T) at 11.5 knots. They also switched on the yacht’s radar.

Shortly afterwards, Riga II’s skipper, who had not yet visually sighted Furness Melbourne, went back on deck to look for the ship. Within a minute, he saw its green sidelight fine on his starboard bow. He decided to alter course to port and, by about 2151, Riga II’s heading had been altered 10º to port. The skipper then altered the yacht’s heading a further 10º to port to a heading of about 280º, with the aim of passing well clear of the ship.

Just after 2153, Furness Melbourne’s lookout reported that the green light he had been observing seemed very close. Riga II was now less than 1 mile ahead of the ship and the two vessels were closing at a combined speed of nearly 18 knots. In response to the seaman’s report, the third mate checked the radar and the AIS unit and saw no target in the direction of the green light.

At 2154, the third mate adjusted Furness Melbourne’s heading to 128º.

Riga II’s AIS unit now indicated that the ship was making good 127º. The skipper’s wife passed this information to the skipper, who exclaimed in surprise to his wife about what the ship appeared to be doing.

At 2155¼, she called Furness Melbourne on VHF channel 16 and identified her vessel as Riga II. The yacht was now about 200 m from the ship’s bow.

Alerted by the unexpected radio call to his ship, the third mate stopped humming. A few seconds later, he broadcast on VHF channel 16 that the ship’s course was being altered to starboard. He then ordered the seaman to engage hand steering.

At 2155¾, the skipper’s wife called Furness Melbourne again and asked its intentions. At about the same time, the skipper saw the ship bearing down on the yacht and shouted for his wife to brace herself.

The third mate responded to the call from Riga II, stating that he was going to starboard and asked for a port to port passing. He could no longer see the yacht’s green light when he ordered the rudder hard-to-starboard.

At 2156, Furness Melbourne’s heading was about 130º when it collided with Riga II in position 19º 35.88’S 148º 01.37’E. The ship’s starboard anchor and/or some part of its flared bow contacted the yacht’s mast and brought it down and the yacht scraped along the ship’s starboard side.

At 2156¼, the skipper’s wife called Furness Melbourne and reported the collision. A few seconds later, she reported that Riga II had been dismasted. The yacht’s navigation lights (mounted on the mast) had gone out and the third mate could not see the yacht. He thought that the yacht was on the port side and, at 2157¼, ordered hard over to port to swing the stern of the ship away from it.

At 2157¾, the third mate ordered the rudder amidships and called the master, asking him to come to the bridge. The master hurried from his cabin to the bridge to find the third mate on the bridge wing looking for a boat he thought the ship might have collided with.

At 2159, the master ordered a heading of 122º. He adjusted the radar’s gain and clutter settings and identified a small target close by on the starboard quarter. He then sighted a dim light in the direction of the target and thought it could be from a torch.

Meanwhile, Riga II’s skipper and his wife were assessing the damage to the yacht. No-one on board was seriously injured. At 2202, the skipper’s wife broadcast an urgency message on VHF channel 16 and then called Furness Melbourne. The master answered her call, exchanged necessary information and advised that he would assist. He then turned his ship around to render assistance to the yacht.

At 2210, Furness Melbourne’s master reported the collision to authorities ashore, advising that the ship was providing assistance to Riga II. The authorities began preparing resources ashore to respond.

By 2300, Furness Melbourne had arrived near the disabled Riga II. The yacht’s sails and rigging had fouled its hull and propeller. The master ordered a lifeboat lowered to assist the yacht’s crew while he manoeuvred the ship to shelter the yacht from the wind and waves.

At 2353, the volunteer marine rescue (VMR) vessel Rescue Bowen departed Bowen to assist Riga II. By this time, Furness Melbourne’s starboard lifeboat was in the water and approaching the yacht with tools that had been requested to cut the rigging that was fouling the hull.

At 0130 on 27 May, Rescue Bowen arrived on the scene and approached Riga II. With Furness Melbourne providing a lee, the VMR rescue crew began connecting their vessel’s tow line to the yacht. By 0206, Rescue Bowen had connected the tow line and, shortly afterwards, began towing Riga II towards Bowen at a speed of about 6 knots.

Furness Melbourne’s crew recovered the lifeboat and, at 0237, after the master had confirmed with authorities that the ship was no longer required to assist, the passage to Portland was resumed.

By 0647, Riga II had been safely towed into Bowen and secured in the marina. In addition to losing its mast, sails and rigging, the yacht’s hull, handrails and paintwork on the starboard side, were damaged. The internal support of the mast had moved, as had some cabinetwork and internal lighting.

Findings on contributing factors to the collision:

• While Furness Melbourne’s lookout sighted Riga II’s starboard sidelight, the officer of the watch was not keeping a proper lookout. He made a series of assumptions based on limited information instead of following a systematic approach to confirm what had been observed. As a result, he did not conclude early enough that the lookout had identified Riga II and that the yacht posed a risk of collision.

• Riga II’s watchkeeper was not keeping a proper lookout. He did not visually identify Furness Melbourne’s navigation lights in time to make an effective appraisal of the situation, did not set the yacht’s AIS unit on a range scale that provided adequate warning of approaching vessels and, when alerted by the AIS of the approaching ship, misinterpreted that information.

Other factors that increase risk:

• In the past 25 years the ATSB and its predecessor have investigated 39 collisions between trading ships and smaller vessels on the Australian coast. These investigations have all concluded that there was a failure of the watchkeepers on board one or both vessels to keep a proper lookout and that there was an absence of early and appropriate action to avoid the collision.

Other findings:

• Riga II was not equipped with a radar reflector or an AIS transceiver unit, either of which would have made it more readily detectable by the watchkeepers on board Furness Melbourne.

In the past 25 years, 60 collisions involving ships and small vessels have been reported to the ATSB and its predecessor, the Marine Incident Investigation Unit. Of these, 39 have been investigated.

The findings from these investigations have invariably included the failure of the watchkeepers on board one or both vessels to keep a proper lookout and the absence of early and appropriate action to avoid a collision.

Safety message:

This incident again emphasises the need for those charged with the navigation of vessels of all types and sizes to keep a proper lookout and to take early and appropriate action to avoid a collision in accordance with the international collision regulations.

The safety lessons from these investigations have been included in the published investigation reports. A number of safety bulletins that aim to highlight the risks and educate seafarers with regard to the similar contributing factors have also been published. These documents and further safety related information can be downloaded at:

www.atsb.gov.au/marine.aspx

Preferred route: The relevant note on the Aus navigational charts states: This is a preferred route and has not been surveyed in accordance with the IMO/IHO standards for recommended tracks, but is the preferred route for vessels having regard to charted depths. The attention of vessels meeting on the preferred routes is drawn to the International Regulations for the Prevention of Collision at Sea (1972), particularly Rules 18 and 28 in regards to vessels constrained by their draught.

If you want to link to this article then please use this URL: www.sail-world.com/117585